how do i make sure the help i offer is acceptable to parents?

You can download these resources and the worksheet as a separate file here (the link is provided again below).

The fourth pathway for expertise looks at the specific expertise and skills involved in ensuring that the help, support, advice and intervention offered is acceptable to parents.

This is based on the Vygotskian concept of common knowledge (see key concept box), and is thus from the same family of ideas as the zone of proximal development (used in effective challenge), and double stimulation (used in escaping impossible situations).

What made the difference between the successful and less successful partnerships we studied was whether the helper understood what mattered to parents and aligned her suggestions and actions with that understanding. ‘What matters’ is a phrase researchers have used in relation to concept of ‘common knowledge’ (see key concept box) and questions of motives [1,2].

This is a mind-expanding process, as the helper learns more about parents, and parents learn new ways of connecting what matters to them with the actions they take.

When helpers stay true to what matters to the parents, specialist expertise can come into productive entanglement with what parents know and their everyday experiences of parenting.

Key concept: Common knowledge

A specific concept of ‘common knowledge’ has been developed by Anne Edwards [1], and connects with other Vygotskian concepts used in this website and the handbook (like the zone of proximal development, and double stimulation). In the context of people collaborating on complex problems (precisely what is involved in working in partnership with parents of children at risk), common knowledge isn’t about everyday knowledge or even having the same knowledge in common.

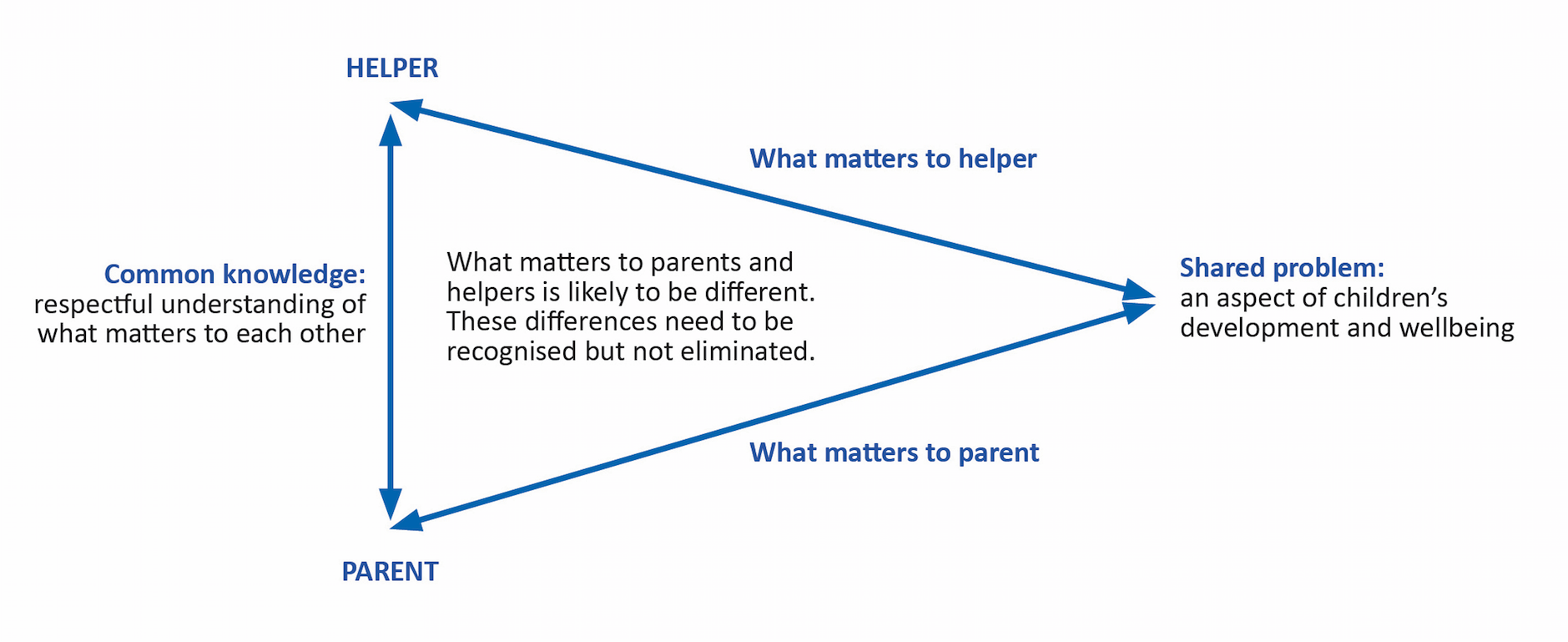

Common knowledge, in the sense used here, is made up of what matters to helpers and parents, the motives that shape and take impactful partnership practice forward [2]. Put most simply, common knowledge is a respectful understanding of others’ motives.

Common knowledge is important because it can represent that there are differences between people working together, and enable them to consider the consequences of these differences for how they should proceed [3].

What matters to parents

Parenting is infused with values and motives about what kind of family to be, and what kind of relationships the child will have with her or his caregivers. ‘What matters’ refers to what parents feel is important, things they are attached to, and aspects of parenting and childhood they value. What matters shapes the aspects that parents may be open to changing or compromising as well as those that are protected and cherished strongly.

Discussing outcomes in terms of children’s learning or parents’ learning with parents can be a useful way to find out what matters to parents.

What matters to helpers

What matters to a helper could be developing the agency of parents in relation to the developmental trajectory of a child (see children's learning as outcomes). It may also be developing particular kinds of relationships (including in building partnerships), and, of course, always, keeping children safe and fostering their healthy development.

Helpers are intimate outsiders in family life. Part of the intimacy involves learning about parents’ deeply held motives and values. Being an outsider means that what matters to helpers will often not be exactly the same as what matters to parents.

One shared focus, different 'what matters'

Impactful partnership does not require what matters to helpers and parents be the same. Working with what matters is not about sameness, but about being explicit about what matters, recognising differences, and aligning responses accordingly. This is why the concept of common knowledge highlights differences (see box).

This is also reflected in the diagram – there are two arrows showing that while the helper and parent are working on the same problem together, what matters to them when doing that work can be different. However, both arrows are converging on that shared problem – showing that these what matters are aligned. If the arrows were parallel, then the partnership would likely run into problems.

why working with what matters requires skill and effort

There are four challenges for the helper working effectively with what matters in impactful partnership:

To have a reflective awareness of what matters as a helper working with a particular family

To make what matters to them explicit and available to parents

To solicit or detect what matters to parents

To align their responses, suggestions, guidance and support with what matters to parents.

Each of these challenges requires both skill and effort on the part of the helper. The first will likely have some consistent features and some that vary depending on the family in question. The others all require deliberate and focused attention during work with parents. We found these may be achieved in very different ways, reflecting helpers’ styles, personality and their assessments of what will work well with these parents in this situation.

what matters and goals

The idea of what matters is related to but different from goals. A goal usually relates to a particular change that can be accomplished, or an end-state that is desired. ‘What matters’ refers to something deeper and more enduring.

For example, a mother may express a goal that her child will settle more easily at night and perhaps remain asleep for longer. What matters to her in this goal may include that her husband can be involved in bedtime routines, which may mean that the settling approach has to accommodate the father’s work schedule. This ‘what matters’ reflects values relating to paternal involvement in child rearing, and motives to share parenting, and for the child to develop strong relationships with both parents. These have an important bearing on what it means to work towards the settling-related goals.

A key finding from the study was that determining goals and then suggesting ways to meet those goals are not always sufficient to secure outcomes through partnership. A helper can offer all sorts of advice, guidance and support that are linked to a particular goal, but these may be rejected by a parent because they don’t address, or may conflict with, what matters.

Sometimes it can seem like defining goals is sufficient, with no need to get into deeper issues of what matters. However, this is an illusion: impactful partnership works when it addresses what matters. When a more surface approach seems to work, this is likely because it addresses what matters, even if this was not explicit or deliberate.

Finding out what matters to parents is different from identifying and negotiating goals. Goals may need to be deliberated on in order to be sufficiently focused or achievable. Exploring deeper motives may require finely-honed skills for helping parents consider their values and priorities. While motives may be deeply held, they may not be talked about often, and may only be at the edges of parents’ conscious thought. Helpers may come to understand what matters to parents indirectly, by listening carefully to how parents respond to particular ideas and suggestions, or by detecting hints from the ways they talk about the challenges they are facing.

an example

The example in the diagram relates to parents at a day stay. Their stated goals were to reduce their daughter’s night waking and increase her solid food intake.

“If there’s a way to help her eat better, and sleep better, we want to know.” (Parent, start of day stay)

What mattered for the parents in the example was child-led parenting and minimal crying. However, this was not discovered until later on in the process. What mattered to the nurse was developing the parents’ capacity. They said they were ‘suckers’ who ‘concede too much’. So, the nurse suggested ways in which they could take more of a lead in settling. Having heard that the parents were force-feeding the child, what mattered to the nurse was also establishing relaxed feeding in which the child had some control.

“I don’t see why this is necessary, we can get her to sleep on her own terms.” (Parent, later in day stay)

Good progress was made in relation to feeding. The helper’s suggestions that the parents let the child feed herself, focusing on making mealtimes relaxed and fun, aligned with the parents’ values of child-led parenting.

However, suggestions relating to settling were resisted by the parents. They felt they were making things harder for their daughter. The helper acted in good faith, offering strategies that aligned with the parents’ goals. But, because what mattered to them wasn’t clear to the helper, the intervention failed.

This shows how important it is for helpers to understand what matters to parents and align interventions with this (a detailed account of this example is available on request [1]).

Back to top | Back to pathways for expertise overview | Previous resource - Impossible situations | Next - What matters (parent-child)

Using the what matters (helper-parent) resources to enhance your practice

The main worksheet is designed for practitioners to reflect on their practice. There is also a version that you may find helpful to use in your actual work with families - this contains the main figure and some key prompts.

Worksheet 11 - What matters (helper-parent) (to print on A4 and complete by hand)

Combined resource and Worksheet (can be completed in the digital file)

References

[1] Hopwood, N., & Edwards, A. (2017). How common knowledge is constructed and why it matters in collaboration between professionals and clients. International Journal of Educational Research, 83, 107-119. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2017.02.007

[2] Edwards, A. (2017). Revealing relational work. In A. Edwards (Ed.), Working relationally in and across practices: cultural-historical approaches to collaboration (pp. 1-21). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[3] Carlile, P. R. (2004). Transferring, translating and transforming: an integrative framework for managing knowledge across boundaries. Organization Science, 15(5), 555-568. doi:10.1287/orsc.1040.0094